Blueprint, Shopping vs Art

Today’s museums cannot afford to see other museums as their only competitors. Lauren Parker of the V&A and Bettina von Hase, art adviser to Selfridges, discuss the role of curator in the retail environment and how it challenges conventional museums.

Lauren parker (above left): The starting point for defining the role of a Curator traditionally comes from the notion of caring for a collection of objects, the sense of being an overseer or guardian. However, even in our national institutions. the idea of What a curator does is changing from a keeper of treasures to include the roles of researcher, writer. commissioner and enabler.

How do you define your specific role at Selfridges? Do you see yourself as a curator?

Bettina von Hose (above right): I see my role much as an intermediary between Selfridges and the artist. My title Is art adviser, but that's a not a complete description of what I do because I’m not buying on behalf of a client. Instead, I act as part creative scout, part commissioner, part producer, and part curator. I am always straddling two worlds, interacting with both art and commerce. I guess I see myself really as a broker between these different worlds, and that’s one of the pleasures of the job

I feel that the art wand has changed to such a degree that a whole new terminology is needed to define roles.

LP: So if you were going to try and define what a curator is now, how would you start?

BvH: I believe that that over the past 15 years museums have really begun to reinvent themselves, to open up and communicate. I see curators less as guardians and more as communicators.

LP: I like the idea of communicating, of opening up a subject to wide audience. I also like the idea of enabling, so that curating becomes not just a one-way process, but a dialogue between artists and spaces, or between art and the visitor, enabling audiences to engage with the work and creating a sense of process not a static experience. How do you feel the experience of seeing art in a retail environment differs to the experience of visiting a museum or gallery? Is there a place for art in a department store?

BvH: The things that work well in Selfridges are projects where people see the making of art. This is really key. I think one of the differences between curating in a public institution or a retail environment is that when people visit a museum they already have it programmed into their minds that they are going to see art – they think they know what they are going to experience. This just isn't the case with Selfridges. Anything artistic is unexpected.

Recent events Include a project which ran alongside the Hayward Gallery’s Africa Remix exhibition. The artist Samuel Fasso installed himself in Selfridges 's corner window in an exact reproduction of his photographic self-portrait, Le Chef qui a vendu I'Afrique aux colons. And following on from the successful run of annual events at Selfridges - from Tokyo Life in 2001 to Brasil 40degrees in May 2004 - we hosted Vegas Supernova in 2005. This featured neon window displays art directed by David LaChapelle, and the interior atrium was transformed into Cathedral of Light by Paul Maffrett.

LP: I am interested in this idea of unexpected encounters between artworks and audiences.

BvH: Selfridges has 17 million visitors a year. If you compare those figures even to, say, Tate Modern, which is extremely successful in terms of visitor numbers with up to five million a year, that's a hell of a lot. The footfall along Oxford Street is enormous and these people are not even necessarily going into Selfridges. However, this also makes the attitude of the visitor different if you do want to present art in this context. I think of it a little like browsing a web page on the internet – you have very little time to engage the viewer's attention, you have to find something that catches their eye or they will have moved on.

LP: What do department stores like Selfridges want to achieve with this? Presumably it isn't just altruism that is driving this programme of activity.

BvH: Obviously. there is a commercial element to this - to attract more shoppers and to encourage them to spend more time in the store. Art projects also work much better than advertising in terms of gaining exposure, from Sam Taylor Wood's XV Seconds project (2000) to Spencer Tunick’s nude installations (2003). Andy Warhol’s famous saying that “when you think about it, department stores are kind of like museums” is becoming true in certain ways. You walk into a store and it's almost as if everything you touch becomes a souvenir of your experience of visiting the store.

One of the reasons Selfridges is so successful in interfacing with contemporary art is because there is no educational threshold to get over. Everyone can relate to a department store, and anyone access it.

LP: One key difference between a department store and a museum is that a store has no obligation to educate the public. Museums want to be seen as entertaining places but, fundamentally, a museum's role is to inspire and educate. How do you think artists see working in a retail environment like Selfridges? Do they find that they are working in a different way?

BvH: Yes, I definitely think that. and that's why I think the programme is so successful — both for the artists involved and for Selfridges. I think first of all that the unexpected element is key. There is also an element of risk. Artists really like that and they like the fact that viewers are not thinking about art when they come Into the store, which can be a refreshing change from the reverential environment of a museum or gallery. It's for everybody, and there is something very democratic about that.

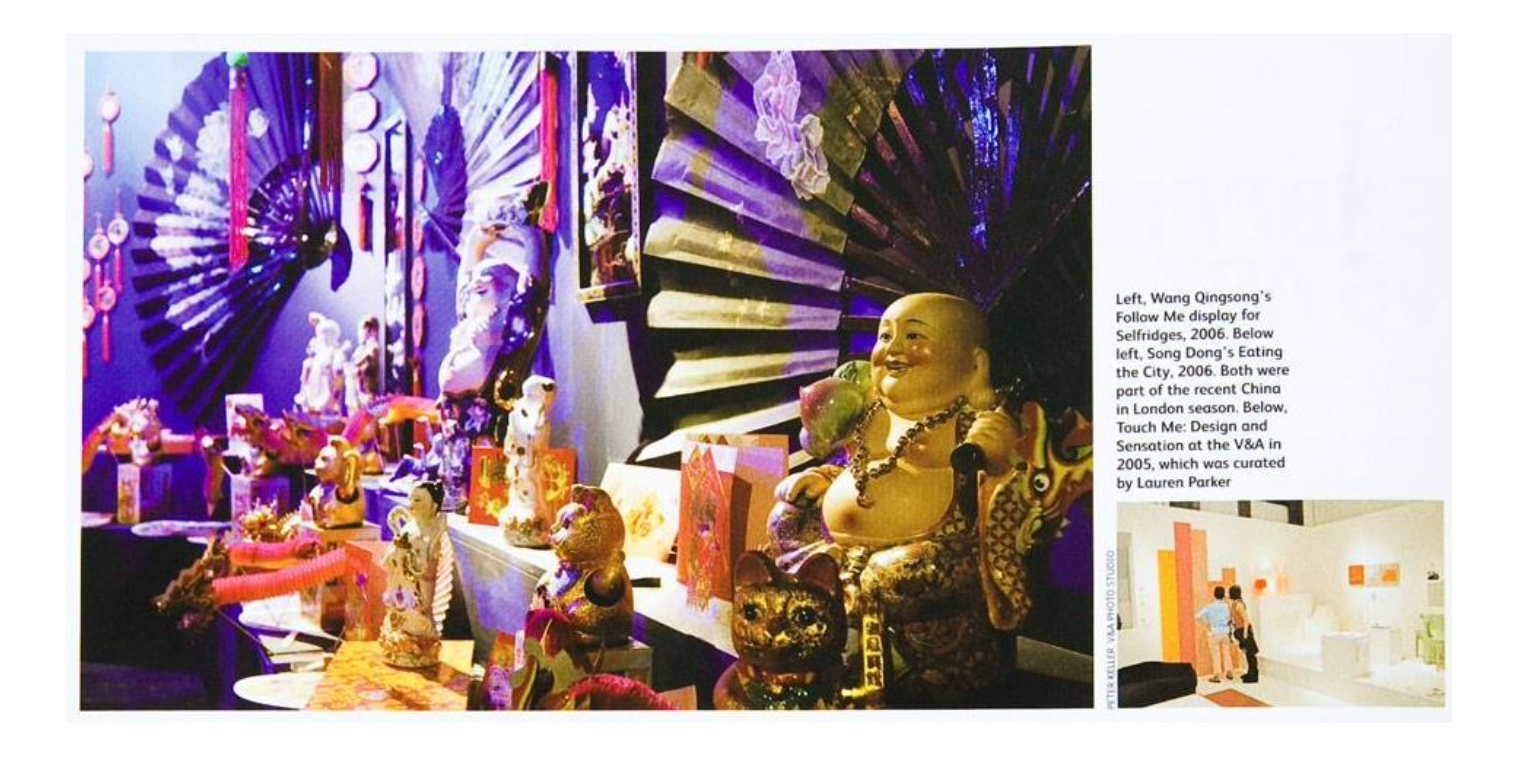

Wang Qingsong's Follow Me series of window displays in 2006 was very interesting project in terms of playing with the retail environment. As part of the recent China In London season he created a huge installation inspired by the global appetite for shopping, which was displayed across the entire run of the Oxford Street windows. He came up with the concept for an investigation into the global obsession with brands, logos and shopping, and he wanted to use products from Selfridges. We immediately thought this would be a great opportunity. And for him it was a critical part of the work that it was shown in a department store.

LP: I think public institutions are also looking at these issues from the other end of the spectrum. There is a need for them to step up to the plate in terms of the visitor experience. The museum shop, the restaurant. new ways of engaging visitors with the museum 's collections and displays — these are all really important.

The contemporary programme has played a large part in trying to democratise the museum experience at the V&A. Friday Lates began in 2000 as a way of offering a different kind of entry point into the museum — presenting live performances, music in galleries, talks. film screenings, late-night bars, DJs and exhibition openings. Five years later, Friday Lates are still attracting up to 6,000 visitors a night, many of whom wouldn't see themselves as traditional museum goers.

This is where some similarities lie between the work that we both do — in trying to engage the viewer and trying to open up these encounters between the space, the artist and the audience. I was really interested in Song Dong 's Eating the City project (2006) at Selfridges because I think that really encapsulates the unexpected, participative and quirky nature of the projects you have worked on.

BvH: The Chinese have a love of food, and when we think of China we think of dragons, dumplings and bicycles — those are three visuals that seem to come into most people's heads. I knew that I wanted to do a project about food as part of the China In London season, and Song Dong was a natural choice.

For Eating the City he created a cityscape made entirely of sweets and biscuits. The biscuit city was incredibly beautiful and such a perfect metaphor for the changes happening in Chinese cities at the moment.

LP: How long did the entire project actually last?

BvH: It was destroyed the moment it was finished! It took five whole days to build and at the end of that period we invited members of the public to come into Selfridges and eat the installation. The eating part only took two hours, and what was interesting to me was that, once it was reduced to biscuit rubble (which it very quickly was), people started trying to rebuild the city, creating tiny versions of houses and streets .It was a truly participative event.

LP: Perhaps the desire to encourage visitors to engage with the art process is a universal one. This discussion reminded me of some of the reasons behind the exhibition Shhh... Sounds in Spaces, which I curated in 2004. We very much wanted to Create a series of dialogues between the artworks, the spaces used in the museum and the visitor. So we commissioned 10 musicians, sound artists and fine artists to create new audio work in response to a range of galleries and other spaces in the V&A.

BvH: -I am interested in this idea of juxtaposing things, of thinking about materials or showing work in new ways. In a way this is what a public institution also does. In your work you invite people to the V&A to reinterpret or enhance or refresh what you have there, to see things with a new eye. I hope my work can do this at Selfridges. Perhaps this an area where we do share the same goals.

Lauren Parker is a curator of contemporary programmes at the V&A in London. She curated the critically acclaimed exhibition Shhh... Sounds in Spaces In 2004 and 2005 's contemporary design show Touch Me: Design and Sensation.

Bettina von Hase is the founder and director of Nine AM. a cultural agency specialising in the conception and realisation of high-quality cultural projects. She is also the art advisor to Selfridges